The National Memorial to the Underground Railroad

Remembering the Underground Railroad

One of the most important stories is that of the Underground Railroad—a testament to the imagination, determination, and sacrifices of those seeking freedom. From the 1830s to the 1860s, women, men, and children risked their lives against slave catchers and oppressive laws. Many traveled north to cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, aiming to join free Black communities, while others journeyed to Canada for true freedom.

The work of the National Memorial to the Underground Railroad is to tell this story and, through it, heal our wounded 10 public memory.

MOVEMENTS INTO BONDAGE

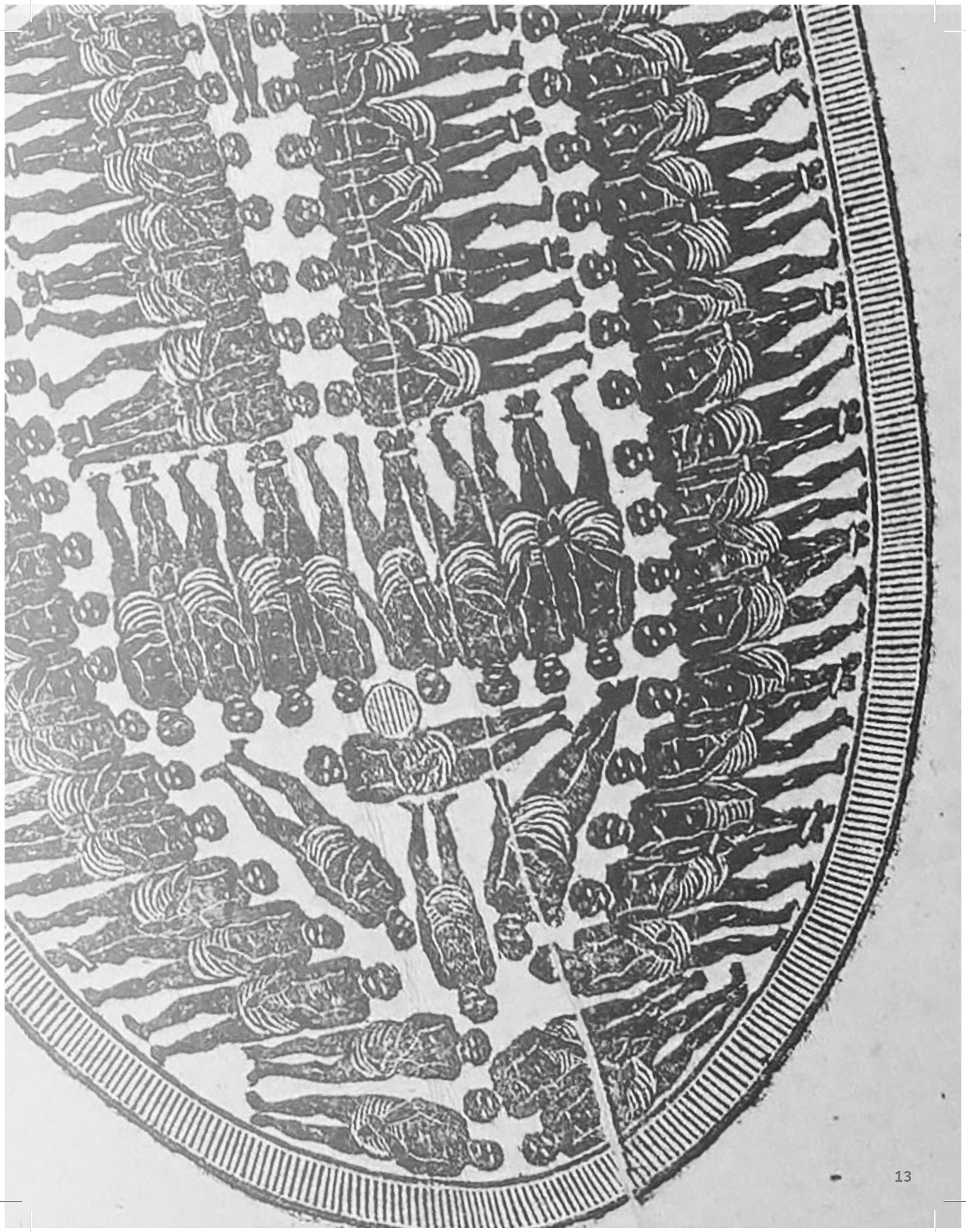

Between 1525 and 1866, 12.5 million Africans were transported across the Atlantic on slave ships, with 10.7 million surviving the journey. Of these, 388,000 were sent directly to North America. The trips varied in length and were marked by scarce food and rampant disease. By 1860, the U.S. had become the largest slaveholding nation, with enslaved Africans contributing vital agricultural knowledge and labor.

They introduced crops like watermelon, coffee, and yams, which were later appropriated and commercialized. Enslaved people were considered property, enduring grueling workdays of 10 to 18 hours under harsh conditions, often facing physical and emotional abuse. Beyond physical escape, they found resilience through song, dance, religion, and cultural practices, which helped them retain their humanity and form a foundation for resistance, influencing their journeys on the Underground Railroad.

MOVEMENTS INTO FREEDOM

From the outset, Africans resisted enslavement, seeking freedom—a central theme of the Underground Railroad. This narrative focuses on Chester County, Pennsylvania, a key area due to its location on the Pennsylvania-Delaware border and the Mason-Dixon Line, making it a vital stop for freedom seekers. Despite its challenging terrain, Chester County offered natural concealment for those escaping slavery.

One significant route was the “Eastern Route,” extending from Wilmington, Delaware, to Philadelphia. Quaker abolitionist Thomas Garrett and free Black abolitionist William Still helped over 8,500 fugitives between 1830 and 1860, collaborating with conductors like Harriet Tubman, who guided many to freedom.

Garrett's home served as the first stop on this route, where freedom seekers would cross into Chester County. They often went to Kennett Square, where they received further assistance. Garrett directed them to various safe houses, including the homes of Isaac and Dinah Mendenhall and the Fussells. Kennett Square was also home to the Longwood Meetinghouse, a key site for abolitionist gatherings. Many Quaker station masters in the area, along with James Walker, a free Black conductor, provided support for freedom seekers. William Still coordinated the Eastern Line and documented the experiences of those who passed through his home in Philadelphia, helping them continue their journeys northward. Additionally, Black churches in the region, including the Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, served as vital stations in the Underground Railroad.

Choosing a Site for the Memorial

The story of the Underground Railroad has global origins and impacts, but focusing on its years (1831-1865) and Eastern and Central lines reveals a narrative concentrated along the Eastern Seaboard. This area, while significantly developed over nearly two centuries, still retains traces of the Underground Railroad era, such as the unchanging Mason-Dixon line that marked bondage and freedom.

To honor and memorialize the people and movements tied to the Underground Railroad, we are exploring several potential sites in Delaware and Pennsylvania. Using GIS mapping, historical research, and on-site documentation, we analyzed these sites based on criteria including:

Locality: Connections to roads, cities, and other Underground Railroad sites

Landscape Diversity: Representation of major landscape types (agriculture, waterways, ecology)

Authenticity: Archaeological or recorded links to the Underground Railroad

Accessibility: Ensuring safety and universal access for visitors

Buildability: Cost considerations for site development

Long-Term Sustainability: Maintenance and management costs

Evaluating these sites through a lens of safety and inclusivity is essential, providing a space for contemplation, memorialization, and celebration for all.

CELEBRATING THE LEADERS OF THE MOVEMENT

For many, the journey to freedom relied heavily on the network of agents, conductors, and station masters along the Underground Railroad. Among the leaders of this network and movement of freedom seekers were a diverse group of collaborators and dreamers who risked their lives and their own liberties for their brothers and sisters.

Harriet Tubman

Frederick Douglass

Sojourner Truth

William Still

Thomas Garrett

Robert Purvis

Freedom Seekers & Allies of the Movement

Between 1810 and 1850, an estimated 100,000 freedom seekers escaped slavery, with names documented by abolitionist William Still in his 1872 book The Underground Railroad. We must remember those who took different routes, were recaptured, or died in their quest for freedom, as well as the millions who remained enslaved

Join the Movement

We invite you to join the movement for the creation of a National Memorial to the Underground Railroad. Like the Underground Railroad itself, this is a journey that we can only take together.